In different eras of art history, artists strived to realistically depict the illusion of space in their own way, using some form of perspective. But what does perspective exactly mean in drawing and painting?

Perspective is applied in drawing and painting to realistically represent three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional drawing surface. By applying the rules of perspective, we can accurately depict the depth of space and the spatial relations of objects in our works of art. In his notes, Leonardo da Vinci expresses the essence of perspective as follows: „The art of perspective is of such a nature as to make what is flat appear in relief”.

The illusion of depth can also be expressed in our drawings and paintings through the use of tonal rendering, light and shadows, colors, positioning and overlapping of elements, gradation of texture, foreshortening, and diminution of size.

Understanding the rules of perspective is a crucial element in mastering drawing fundamentals. By skillfully applying these principles, we can elevate our artworks to a professional level. Whether working with traditional materials and techniques or digital tools, a solid understanding of perspective is an invaluable artistic technique.

How Do We Perceive Art?

The world we live in exists in three dimensions: length, width, and height. Due to the structure of our eyes, we see in only two dimensions. However, based on our experiences, the brain interprets what we see as three-dimensional.

Using the same principle, we are capable of perceiving two-dimensional works of art as three-dimensional if they contain the necessary visual cues. When we create or observe art, our brains engage in a complex process of interpretation. The way we perceive depth and space is influenced by various psychological factors.

Moreover, the emotional and cultural context also influences our perception of art. Artists, knowingly or intuitively, tap into these psychological processes to guide the viewer’s perception.

- Artists often use linear perspective to create an illusion of depth. This involves drawing converging lines that meet at a vanishing point. Our brains interpret these converging lines as depth, mimicking the way parallel lines seem to converge in the distance in reality.

- In aerial perspective, objects in the distance appear hazier and lighter in color due to the atmosphere. Our brains interpret this as depth, as distant objects seem less distinct. Objects that are closer to the viewer often appear more vivid and have intense, saturated colors. As objects recede into the distance, the air between the viewer and the object scatters light, causing a shift in color perception. Distant objects tend to appear cooler in tone, and less saturated.

- Our brains also use size, overlapping, and foreshortening as cues for depth. Objects that are closer appear larger, and when one object partially overlaps another, we perceive the overlapped object as farther away. Foreshortening involves drawing objects shorter to effectively convey a sense of depth.

- The level of detail also plays a role in how we see distance. Objects in the foreground often have more distinct textures and finer details, while those in the background may have less detail. This mimics the way our eyes perceive and focus on nearby objects with greater clarity.

- The positioning of an object in a work of art can act as a depth indicator through several visual cues. Placing objects closer to the bottom of the composition tends to create a sense of foreground, suggesting proximity to the viewer. Objects positioned higher in the composition can convey distance or background.

- The depiction of light and shadow makes flat surfaces appear as if they are three-dimensional. Artists manipulate contrasts between light and dark areas to enhance the illusion of volume and form in their work. This technique is often referred to as chiaroscuro, used by Rembrandt and Caravaggio.

I highly recommend Robert L. Solso’s book, ‘The Psychology of Art and the Evolution of the Conscious Brain,’ if you are interested in learning more about how we perceive art.

Types of Perspective

The application of perspective in the pre-Renaissance ages was empirical. However, in the 15th century, the great masters of Renaissance art developed linear and atmospheric perspectives, as well as color perspective—all of which are still in use today.

Linear Perspective

As objects move closer to us, our eyes converge, meaning they turn slightly inward. Artists mimic this by using converging lines in drawings to create the illusion of depth. In linear perspective, parallel lines appear to meet at a vanishing point, replicating the way our eyes converge on nearby objects.

The elements of linear perspective include:

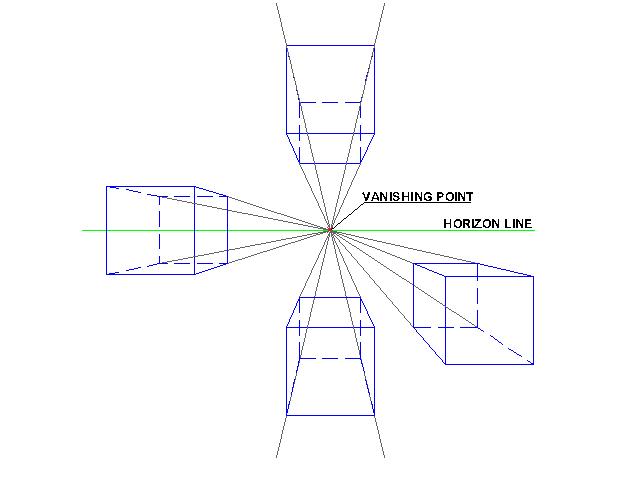

- The horizon line is always at the eye level of the observer.

- The vanishing point (there can be more than one in a drawing) is located on the horizon line. Sometimes, the vanishing point extends beyond the drawing sheet and cannot always be determined within it.

- Orthogonal lines converge at the vanishing point.

- Transverse lines are parallel to each other and to the horizon line.

The following rules apply to the linear perspective:

- Moving towards the vanishing point, the objects appear smaller and smaller, as Leonardo explained in his notes:

„Linear Perspective deals with the action of the lines of sight, in proving by measurement how much smaller is a second object than the first, and how much the third is smaller than the second; and so on by degrees to the end of things visible.”

„The object that is nearest to the eye always seems larger than another of the same size at a greater distance.”

„Small objects close at hand and large ones at a distance, being seen within equal angles, will appear of the same size.”

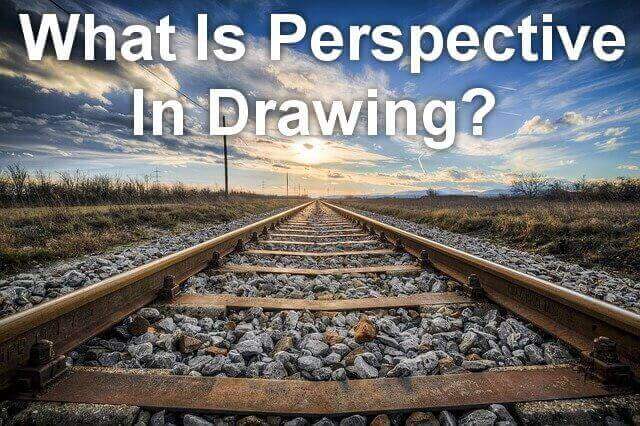

- As objects converge toward the vanishing point, the distance between otherwise equidistant objects decreases. This phenomenon is often illustrated using the example of railway track sleepers.

- Objects appear in their real size when perpendicular to the viewer’s line of sight (parallel to the picture plane). When they turn away, shortening occurs.

- Elements closer to the viewer partially cover those located further back in space.

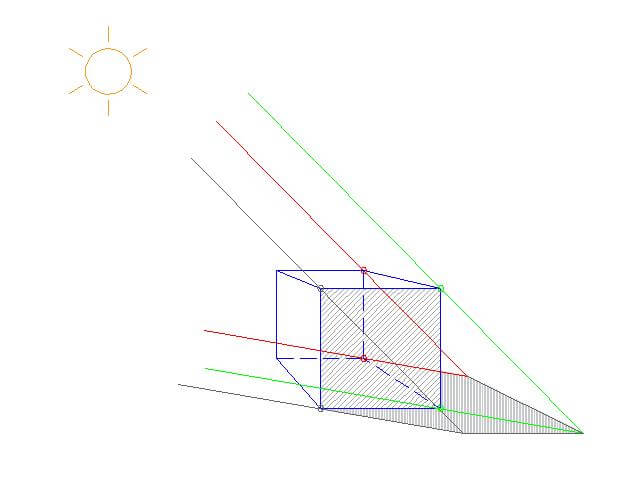

- To illustrate the three-dimensional nature of objects, we can also display the effects of light and shadow on our drawings.

- Objects may be located at eye level, below, or above the horizon line.

One Point Perspective

The cube is the simplest geometric body, so it is often used to illustrate the principles of the one-point perspective.

We look at the object exactly from the front. The otherwise parallel lines of the side planes meet at one vanishing point located on the horizon line. The depth of the object is shortened, but the height and width on the front plane do not change.

Two Point Perspective

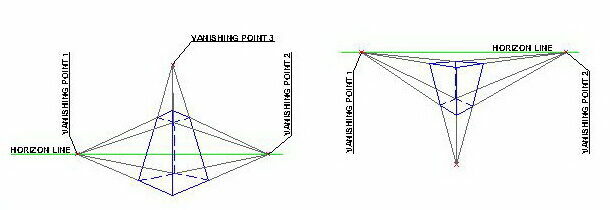

Let’s take the cube again as an example. In a two-point perspective, we see two sides of the cube with one edge pointing toward us.

The orthogonal lines converge towards two vanishing points on the horizon line. In this case, the vertical lines of the elements remain unchanged and all the other lines converge toward the vanishing points. The depth and width of the objects are shortened.

Three Point Perspective

A three-point perspective is used to represent a very tall object or a large depth, such as a tall building observed from below or a cityscape from above.

In this case, in addition to the two vanishing points defined on the horizon line, we also define a third one that is below or above the horizon line.

The third vanishing point also allows you to draw objects in an oblique plane, such as a roof.

Atmospheric perspective

In reality, the atmosphere scatters light, making distant objects appear lighter and hazier. In his notes, Leonardo da Vinci defined in detail the rules of atmospheric (aerial) perspective.

The rules of atmospheric perspective are as follows:

- Due to the influence of the atmosphere, the outlines of more distant objects are depicted as less sharp than those closer to us.

- As the object moves away from us, we draw less and less detail.

- The colors of objects closer to us are more vivid. As they move away, the colors become more and more neutral.

- As a result of the atmosphere, the tones become brighter and the colors more bluish as the object moves away from us.

Leonardo da Vinci masterfully applied atmospheric perspective in his painting The Virgin and Child with St. Anne.

Color Perspective

Colors can express the depth of space and the spatial position and distance of objects. On the same background, warm, saturated, and light colors appear closer than cold and dark colors.

According to Leonardo: „A dark object seen against a bright background will appear smaller than it is. A light object will look larger when it is seen against a background darker than itself.”

Perspective Development Through Art History

It has always been a challenge for artists to depict the 3-dimensional world on a flat surface in an authentic, believable way. Some form of representation of space has always been present in artistic practice.

In the course of art history, several methods have been developed for the visual representation of the illusion of space and depth.

Prehistoric Art

The prehistoric artist has already tried to creatively solve the problem of depicting space in cave drawings.

In the composition representing bison in the Lascaux cave, we can see how the planes located at different depths in space were separated by the artist. It is clear that the bison in the foreground partially covers the animal further away in space.

The hooves of the bison in the first plane are elaborated in detail, while those in the background appear only at the level of outlines.

Ancient Civilisations

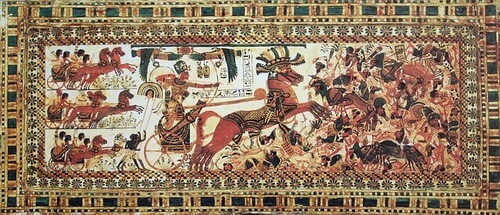

In ancient Mesopotamian, Assyrian, and Egyptian art, space was depicted in the form of bands on which objects were arranged side by side.

Ancient Greek and Roman artists mostly relied on techniques such as overlapping, diminishing size, and atmospheric perspective to represent depth and three-dimensionality. However, these techniques were more intuitive and observational, rather than based on a formalized system of perspective as seen in later art periods.

Depicting Space in Ancient Egyptian Paintings

The differences in the size of human figures in Egyptian murals did not primarily reflect their spatial position, but their place in the political and religious hierarchy. Therefore, the figure of the pharaoh is always the largest.

Photo by Chaos07 via Pixabay

The vertical perspective was a more advanced way of representing the depth of space. In their paintings, the Egyptians depicted the elements on several bands lined up one above the other. The different rows represent objects located at different depths of space, with the bottom row containing the elements closest to the viewer.

Egyptians also applied partial overlap of objects to create the illusion of depth in their paintings. For more information on Egyptian art, you may wish to read my article on why Egyptian artists opted for twisted/mixed perspective.

Depth and Distance in Ancient Greek and Roman Art

The desire to depict three-dimensional space also appears in ancient Greek art. The technique used in the stage scenery depicted the depth of the space by painting larger shapes in the foreground and a smaller cityscape in the background.

The perspective representation in the murals found in Pompeii and Herculaneum is similar to the ancient Greek stage scenery, with larger elements in the foreground and a smaller cityscape in the background.

The fresco in one of the villas in Herculaneum is made from a one-point perspective, but the orthogonal lines move in the direction of not one but several vanishing points.

The aerial perspective also appears in this ancient Roman mural, as the elements in the background are less vivid and bluish, giving the impression that they are distant.

Representation of Space in Medieval Art

There has been a decline in medieval art since ancient times, and ancient knowledge of perspective has been forgotten. In medieval painting, two-dimensional representation was used, in which objects were arranged in a vertical direction.

The size of the human figures in medieval works of art, just as in ancient Egypt, sometimes depends on their importance rather than their spatial position.

The inverse (reverse) perspective was used in pre-renaissance eras in Byzantine religious art and Orthodox iconography. In the inverted perspective, elements closer to the viewer are depicted as smaller than those farther away.

The reverse perspective differs from the linear perspective in that the vanishing point is located in front of the image plane, on the side of the viewer. This gives the impression that the space opens up in front of the viewer.

Parallel perspective or axonometry was also a common technique in medieval art.

In Paolo Veneziano’s painting of Saint Nicolas, we can see the use of the inverted perspective (image on the left) and the parallel perspective (image on the right).

Perspective in Renaissance Art

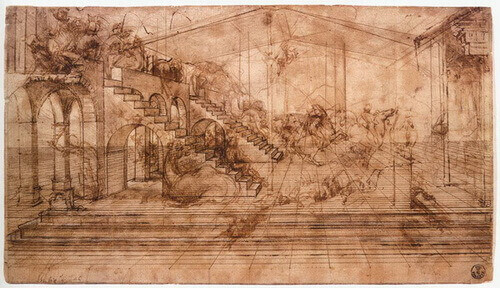

After its decline in the Middle Ages, perspective was rediscovered during the Renaissance and its development was elevated to a scientific level. The development of linear perspective began with the work of two Italian architects, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Leon Battista Alberti.

In Renaissance painting, perspective served a variety of purposes—it presented spatial depth, created illusions of dimension, and directed the viewer’s gaze to key details. As a result, the vanishing point would occasionally align with a crucial element in the artwork, such as the head of Christ coinciding with the vanishing point in Leonardo’s Last Supper.

In his notes, Leonardo da Vinci analyzes in detail the principles of linear perspective. Da Vinci also deals with shadows, color perspective, and aerial perspective.

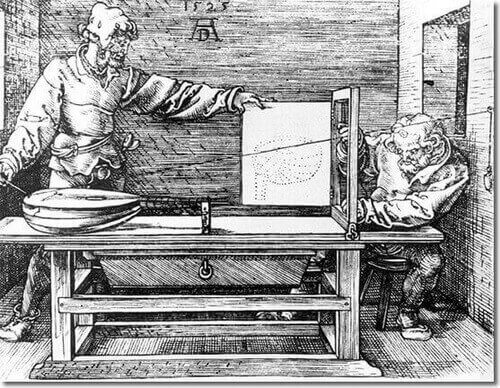

The use of perspective was also adopted by the Flemish artists after the Italians. In Western European art, Albrecht Dürer applied perspective to his works. He made woodcut illustrations of different techniques for applying perspective.

In Renaissance paintings, subjects are consistently positioned behind the picture plane, as if we’re peering through a window, following Alberti’s definition of perspective.

While Renaissance artists seldom portrayed objects in front of the picture plane, there are exceptions. In Jan van Eyck’s diptych “Annunciation,” sculptures are depicted as if they stand before the frame, creating the illusion of them stepping out into the space in front of the picture plane.

Moving into the Baroque era, Caravaggio’s “Madonna di Loreto” depicts human figures portrayed in front of the picture plane.

In the following centuries, mathematicians worked to define the geometric method of linear perspective still in use today.

Final Thoughts

The necessity for a realistic representation of the three-dimensional reality around us has led to the development and application of perspective in drawing and painting.

Using linear, atmospheric, or color perspectives allows us to convey spatial effects in our art, to achieve a convincing illusion of depth. Perspective is a fundamental aspect of drawing, offering further benefits such as leading the eye through the composition and conveying mood, regardless of the medium—traditional or digital.

Join the conversation by leaving your thoughts in the comments below! If you found this content insightful, share it on your favorite social media platforms. And don’t stop here—explore more captivating articles on our website to deepen your understanding of art fundamentals.

Debora

My name is Debora, and I’m the founder of Drawing Fundamentals. I work as a civil engineering technician. I acquired the basic knowledge necessary for freehand and technical drawing during my school training, further developing and perfecting these skills throughout my years in the profession. Through my blog, I aim to assist anyone interested in learning to draw.