In ancient art, the depictions of space mostly relied on a naturalistic and intuitive understanding of how objects and figures related. They didn’t use the formalized system of perspective as we know it today. In some ancient cultures such as in Egypt, symbolism was strongly emphasized over realistic representation.

In this article, we aim to explore the various techniques used by ancient civilizations to depict space and depth, which predated the mathematical system of perspective in art

Actually, ancient artists did use some elements of perspective, but the systematic application of linear perspective as we understand it today didn't become widespread until the Renaissance. In ancient art, especially in ancient Greece and Rome, artists often applied foreshortening, overlapping, and atmospheric perspective to create a sense of depth. However, their approach to depicting space was more intuitive and less grounded in mathematical principles.

The Development of Perspective Through Art History

In ancient art, particularly in cultures such as ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, symbolism was strongly emphasized rather than realistic representation. The art of these civilizations served various purposes, including religious, political, and social.

It’s worth noting that the concept of linear perspective in the mathematical sense, as we understand it today, was not present in ancient art. Their techniques for conveying space and depth were intuitive.

The shift from intuitive toward systematic linear perspective, with defined vanishing points and geometric precision, appeared during the Renaissance, particularly with the contributions of artists like Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti.

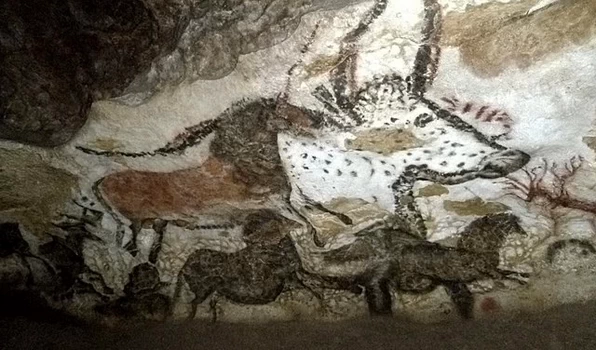

Depiction of Depth in Prehistoric Art

Even in the archaic period, there was a degree of spatial representation, as we can observe in the Hall of the Bulls of the Lascaux Cave.

Prehistoric artists depicted these animals with a sense of perspective, showing some in the foreground and others in the background. This suggests an early understanding of spatial relationships.

The strategic placement of animals on different parts of the cave walls also contributes to the perception of depth and conveys a sense of movement. Some are positioned higher, some lower, creating a varied landscape.

Among the techniques used in the Lascaux paintings for suggesting depth is overlapping. You’ll notice that some figures are superimposed on others. This creates a natural sense of foreground and background, giving the impression of spatial depth.

The level of detailing and shading on the animals is not uniform. Animals in the foreground often have more detailed features and shading, making them visually distinct from those in the background. Shading helps to create a sense of volume and form.

Mesopotamian and Egyptian Art

While distinct in many aspects, Mesopotamian and Egyptian art share some common features due to their geographical proximity and interactions.

They both used the technique of composite perspective, where a single artwork contained different viewpoints. The idea was to showcase humans, animals, and objects from the most characteristic and easily recognizable angles.

The depth of space was mostly conveyed by placing subjects farther in the space above those in the foreground. Depictions of everyday life scenes sometimes feature overlapping figures to create a sense of depth.

Pharaohs, kings, and gods were often portrayed as larger than other figures, not necessarily because of their spatial proximity but due to their elevated status.

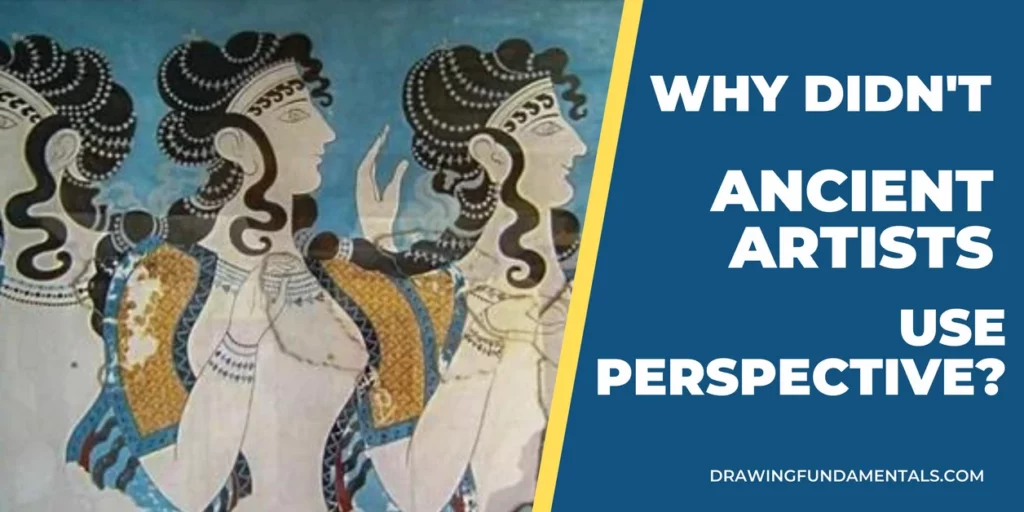

Minoan Culture

The spatial representation in Minoan art can be observed in the frescoes of the Knossos Palace. These paintings share some similarities with Egyptian art but are slightly more dynamic. Primarily featuring stylized people, animals, and plants, the frescoes maintain a completely two-dimensional quality, without the depiction of light and shadow.

Ancient Greece

Original works of Greek painting are nearly non-existent today, leaving vase painting as our primary source to understand its characteristics and development. In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, vase decoration relied on linear, geometric elements, portraying small and stylized human and animal figures.

In the 6th century BCE, Athens took a leading role in the arts, including pottery. Based on the vase painting, we can conclude that Attic artists used visual representation tools sparingly: they conveyed spatial distance through size differences and indicated direction through suggestive movements.

The desire for realistic representation in artworks began with the ancient Greeks and gradually evolved. Artists became increasingly adept in anatomy, movement, and perspective, leading to advancements in spatial representation in art.

Ancient Rome

We know quite a bit about the wall paintings of ancient Romans, as the artistic heritage of the region was preserved by volcanic ash. In places like Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae, mural painting developed continuously from the 2nd century BCE. Villas were decorated with paintings depicting colonnades, stage-like scenes, and depictions of flora and fauna.

A set of frescoes can be seen as illusionistic architectural images, where artists instinctively applied perspective using converging lines, giving the impression of real space. In these paintings, we encounter a form of perspective in which the details depicted in foreshortening, represented by orthogonal lines, do not converge to a single focus.

In this case, the vanishing points are positioned along a vertical axis, and the orthogonal lines are generally parallel to each other. This form of spatial representation is called orthogonal or axial perspective. Its advantage lies in providing a credible sense of space in depicted structures, with their foreshortened details not overly distorted. However, they still do not precisely correspond to the depiction of observed reality.

Another set of images portrayed still lifes, animals, people, architectural details, landscapes, and plants. Unlike earlier instinctive perspectives, landscape paintings conveyed the depth of space through overlapping, color, and atmospheric perspective.

Early Christian and Byzantine Art

The catacomb paintings representing early Christian art were not created by trained painters but rather by skillful community members, lacking depictions of space and background. Later, Byzantine art also did not strive for realism; icon painting followed strict compositional rules and depicted rigid, schematic figures.

The lack of realistic depiction of space and depth continued through the medieval period. During the Middle Ages, the representation of space generally wasn’t a significant concern for artists. In Romanesque painting and miniature art, the depth of space was, at most, suggested, but the norm was to unfold spatial forms onto a flat surface. This trend has its roots in Late Antique and Early Byzantine mosaic art dating back to the 4th-6th centuries.

As the Renaissance approached, there were gradual shifts in artistic styles and techniques. In the Italian painting of the second half of the 13th century, the depiction of space once again plays an important role, setting the stage for the changes that would take place during the Renaissance era.

Perspective in the Renaissance

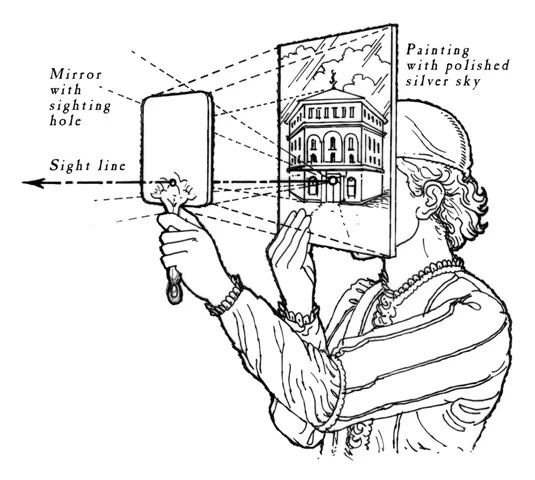

The Renaissance was a period of cultural and intellectual transformation in Europe, and one of its significant contributions was the innovation in artistic perspective. Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti developed the mathematical systems of linear perspective.

Brunelleschi realized that objects appear smaller as they recede into the distance and that parallel lines converge at a vanishing point on the horizon. These principles are the foundation of linear perspective as we know it today.

Alberti outlined a mathematical system for creating perspective in art. He introduced the concept of a geometric vanishing point, providing artists with guidelines for constructing realistic architectural spaces and representing depth accurately.

Leonardo da Vinci perfected the use of atmospheric perspective to a masterful degree. This technique involves using a shift in color and tone, and sharpness to mimic the atmospheric effects on how we perceive distance.

Final Thoughts

While ancient artists didn’t use the formal perspective we know today, they intuitively applied perspective methods such as foreshortening, overlapping, and atmospheric perspective. The Renaissance marked a shift, introducing mathematical principles that are still in use today.

If you found this blog post interesting, we’d love to hear your thoughts. Leave a comment below, share this article on your social media, and feel free to explore more captivating articles on our website.

Debora

My name is Debora, and I’m the founder of Drawing Fundamentals. I work as a civil engineering technician. I acquired the basic knowledge necessary for freehand and technical drawing during my school training, further developing and perfecting these skills throughout my years in the profession. Through my blog, I aim to assist anyone interested in learning to draw.